Numbers Geek: Steve Ballmer on the U.S. trade deficit, China’s role, and the impact on the economy

How big is the U.S. trade deficit, in reality, and what are the implications of U.S. trade negotiations with China and other major countries around the world?

On this new episode of the Numbers Geek podcast, we dive into the numbers behind the U.S. trade deficit, the trade war with China, and the implications for the U.S. economy, with our resident Numbers Geek, former Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer, the founder of our podcast partner USAFacts, the non-partisan, non-profit civic data initiative.

Listen to the episode above, or subscribe to Numbers Geek in your favorite podcast app. Continue reading for a full transcript of the episode, plus graphics from USAFacts showing the key numbers behind this issue. Also see page 46 of the USAFacts 2018 annual report for a deep dive on U.S. trade numbers.

Steve Ballmer: Exports minus imports is negative. And if you want to call that a deficit, if you want to call that an imbalance … you know, I call it A minus B is less than zero. That’s all that really matters in this case.

Todd Bishop V/O: That is Steve Ballmer, the former Microsoft CEO, and the founder of USAFacts. On this podcast, he is our resident numbers geek, and he’s explaining the formula behind one of the most closely watched numbers in the country right now, the U.S. trade deficit. If only it were that simple. Just listen to all the numbers flying around on this one.

News Clip One: At the stroke of midnight, the U.S. hit China with tariffs on $34 billion worth of goods.

President Trump: Our country lost $800 billion last year with trade generally.

News Clip Two: Last year, the world’s two largest economies traded an estimated $579 billion in goods.

Todd Bishop V/O: Coming up, we will dive into the numbers behind the U.S. trade deficit, the trade war with China, and the implications for the U.S. economy. From GeekWire and USAFacts, this is Numbers Geek. I’m GeekWire Editor Todd Bishop. Stay with us.

Todd Bishop: Hey Steve, it’s great to see you.

Steve Ballmer: Great to be here, Todd.

Todd Bishop V/O: We started our conversation with Steve with a basic explanation of the trade deficit.

Steve Ballmer: Every year, we export and import some goods. So maybe we import some electronic devices that were made in China. That is, we send money to China. China sends us the good. Similarly, perhaps we export Boeing planes. They’re made here. We send them outside the country, and money comes back in to this country. So you get this notion of exports and imports. We are importing, we are sending more money out, if you will, than we are taking back in.

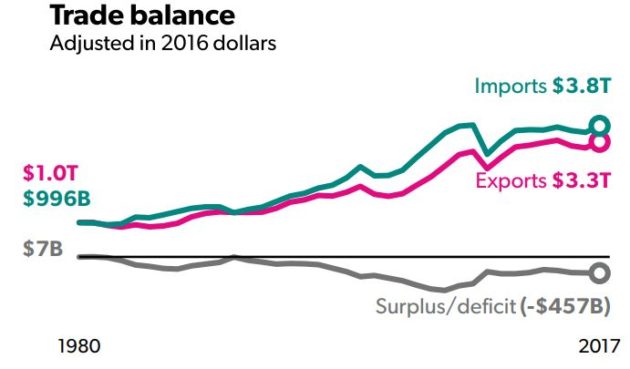

Todd Bishop V/O: So here is the big picture. In 2017, the overall U.S. trade deficit … remember that’s the amount by which imports exceed exports in U.S. trade with countries around the world. That number was $552 billion, up 10 percent from the prior year. That’s when counting both goods and services. So to put this in context, the trade deficit is in the range of 2.5% of U.S. gross domestic product, or GDP. That’s the country’s annual output. That $552 billion trade deficit for 2017 was down from $762 billion in 2006, but up from $384 billion in 2009, during the recession.

That combination of goods and services, $552 billion as the trade deficit, is the number you will hear most often in the press. But in its annual report on the U.S. government, USAFacts uses a bigger picture calculation of the trade deficit. Its calculation takes goods and services, but then adds in income from American citizens working in other countries. Steve explained why that’s important.

Steve Ballmer: The top American export is actually American citizens who are working abroad. They are making money abroad, and they are sending it back to the U.S. In a sense, you could say those people are exports. We’ve sent them some place. They are earning and they are bringing back money to the United States. Now they’re not a good, they’re not like a car, but it’s something you send abroad and for some period of time, it brings back money.

Similarly, if you look at it the other way, foreign citizens working in the United States are our biggest import. These are both numbers essentially around $1 trillion. Total imports into the country are about $3.8 trillion. So these are significant numbers in the grand scheme of our total exports and imports.

Todd Bishop V/O: That bigger picture view put the U.S. trade deficit in 2017 at $449 billion. Now, obviously that is still a deficit, but it’s lower than the $552 billion deficit that you get from counting goods and services alone. That’s because the income from Americans working abroad exceeds the income from foreigners working in the United States, which gives the U.S. a net surplus in that specific category of global trade, lowering the overall deficit.

Okay, so that is Americans working abroad sending income back to the country, paying taxes here in a lot of cases. What about actual goods and services to some extent? Let’s run down the rest of this list.

Steve Ballmer: Our biggest non-people export is capital goods. Capital goods … we’re not counting automotive, that comes elsewhere. But capital goods are something that doesn’t get used up quickly. When a family buys a capital good or a factory buys a capital good, it will stick around for a while. So excluding cars, $533 billion of exports of capital goods, you can turn it around and look though the other way. We are importing $644 billion worth of capital goods. So we are a net importer, we run a net deficit, if you will, of capital goods.

In the case of people working abroad, we run a net surplus.

Todd Bishop: Let’s actually look at the numbers, at the facts-

Steve Ballmer: OK, let’s do it.

Todd Bishop: … to see what happens. First off, imports and exports by country between the U.S. and other countries. We are ranking these by total exports. And at the top of the list, in other words, the country to which the U.S. exports the most, it’s Canada, and then followed by Mexico. So this looks like a healthy trade relationship with both Canada and Mexico based on these numbers.

Steve Ballmer: Well, they both are what they are. I mean, at the end of the day, you will have surplus with some people. You will have deficit with others. In the case of Canada, we run a small surplus as opposed to a deficit. You can see here, we export $409 billion, and we import $395 billion. Roughly in balance. Not per se an important number, but if you look at things in aggregate, things get important. With Mexico, and this should be no surprise, NAFTA made the situation ripe for Mexico and Canada to be our two biggest trading partners. We do export less than we import from Mexico. With the UK, we run a surplus, $242 billion to $194 billion. Then you get the big deficit, which is what we run with China, which is where trade is the least fair, I would say, by my own experience running Microsoft.

Todd Bishop V/O: Counting goods, services and income earned by American citizens overseas, the trade gap with China in 2017 was $358 billion, representing more than 79 percent of the overall U.S. trade deficit of $449 billion for the year. We explored the issue of the U.S.-China trade deficit by looking a February 2018 news article specifically about the trade gap in goods, using the official numbers at that time.

Todd Bishop: So this is from the New York Times, “U.S.-China trade deficit hits record, fueling trade fight.” They explain that “The gap between Chinese goods imported to the U.S. and American goods exported to China rose to $375.2 billion last year.” Now, I hear that number, Steve. Right off the bat, I think that’s pretty big. What do you take away from this story in terms of the numbers and the facts?

Steve Ballmer: A way to put the $375 billion in context is to take a look at the value of everything that is produced in this country per year, which is our gross domestic product, or GDP. That number’s about $20 trillion, if you will. So you do the math, and that says something like 1.5% of everything we make, we somehow have pledged to people outside the United States. And that’s just to the Chinese. In total across the world, we are cutting into our principal, our future earnings, our assets by about 2.5% a year. It is what it is. Some people can call that consequential. Some people’ll think that’s small. But if you do 2.5% for a long time, that doesn’t sound very good in terms of what you have left.

Todd Bishop: But this sentence is what really struck me. “Economists said the growing trade deficit stemmed largely from the strength of the U.S. economy, which helped American consumers afford more imported electronics, clothes, and appliances.” That sounds like a good thing though.

Steve Ballmer: Well, there’s some goodness in that. But where’s the money coming from in the United States to buy these things abroad? Part of our great economy and the way we’re living is because we are borrowing money. We’re borrowing from the rest of the world, and the U.S. government borrows from the rest of the world, and the U.S. government borrows on all of our behalf.

So the budget deficit and the trade deficit are both part of bringing more money in than we really can afford and pumping up the economy. It is a sign of some good things, but it does not speak to a health in our economy on the sell side.

Now some of that is for other reasons. As a guy who used to run a software company, I know our software was being stolen to the tune of tens of billions in China when I left Microsoft five years ago. Well, $10 billion looks pretty big compared to that $375 billion deficit with China. So some of that is because of, let me call them, unfair trade imbalances based around proper recognition of intellectual property.

Todd Bishop V/O: We will explore the implications for the U.S. economy after the break.

We are discussing the U.S. trade deficit this week. It is a key topic in the news right now, because of the ongoing negotiations between the U.S. and China to reach a new trade agreement, and the impact of tariffs on U.S. businesses in the meantime. Let’s jump back into our conversation with Steve Ballmer, the former Microsoft CEO, the founder of our podcast partner USAFacts, and our resident numbers geek, who you might have noticed has a specific viewpoint on this issue.

Todd Bishop: So essentially, over time we have been bringing in more goods than we’ve been selling to other countries.

Steve Ballmer: That’s correct.

Todd Bishop: Is that a problem?

Steve Ballmer: When we run a trade deficit, we are essentially either selling assets in the United States, or we are selling off part of the future earnings of Americans to somebody else or somebody elses in other countries. We are sending more money out, if you will, than we are taking back in.

And what do people do with that money, that additional money that we are essentially borrowing from them? They take that in the form of IOUs or purchases of land and factories and businesses here in the United States. It is literally like selling off some of your savings every year in order to support your current lifestyle.

Take it in your own personal life. If I said to you, “The only way for you to sustain your lifestyle was to essentially sell off all the stocks and bonds you own,” and you do it over a course of a 10-year period, and all you have left at the end of that 10-year period basically is a house. Then over the next 10 years, you sell off your house, you eat into all that money. So now 20 years from now, you have nothing except your ability to work. And you might say, “Hey, that’s kind of not the way I’d want to manage our affairs.”

The country has that same issue. We continue to essentially live off of the sale of things here, or by borrowing money from somebody outside the country. And in that process, we are turning over either our future earnings or some assets that we own to somebody who is outside the United States. And that is a tricky proposition.

Todd Bishop: Steve, I know that USAFacts presents the facts and lets people decide. When I’ve talked to you about things like the budget deficit and the trade deficit, it sounds like you have an opinion on this one.

Steve Ballmer: On the budget deficit, I think there’s a real problem. I think the U.S. government cannot run a deficit for the long term. Now, that’s a personal opinion. The data’s all there in USAFacts for people to come to alternate opinions. There are certainly economists who would agree with me and disagree. I’m just a business guy who doesn’t understand how you continue to increase your borrowing and borrowing in perpetuity, just as I don’t understand how, in the case of trade, we continue to either borrow or sell off parts of our country.

Now, the trade deficit, a little different than the budget deficit. On the other hand, they both, in a sense, mean that we are either living beyond our means, or we just don’t have the goods the rest of the world wants to buy. So we’re having to sell parts of the United States as opposed to goods to those countries.

Todd Bishop: There are, as you said, economists who actually don’t see the trade deficit as a negative on the same level as the budget deficit. And in fact, there’s a debate out there over whether the trade deficit should be called a deficit, that perhaps that’s a loaded term in this context, and we should call it an imbalance instead. You look skeptical.

Steve Ballmer: Well, call it whatever you want. Exports minus imports is negative. And if you want to call that a deficit, if you want to call that an imbalance, I call it A minus B is less than zero. And that’s all that really matters in this case.

Todd Bishop: Is there any correlation, is there any way for us to draw a correlation between the overall trade imbalance or deficit, pick your term, and GDP over the years?

Steve Ballmer: Well, one of the things you have to remember is GDP equals all the things that we produce for consumption plus all the things we produce that’s capital investment by businesses plus all of the government spend on things like police and defense, not transfer payments back to consumers. But then on top of that, you’ve got to add exports, and you have to subtract imports. So GDP is not independent of the trade deficit. The trade deficit shows up as a lowering of GDP.

Todd Bishop: So if you’re actually importing more than you’re exporting, then your GDP will be lower?

Steve Ballmer: Correct.

Todd Bishop: Steve, I want to ask you what you would do about all this if this were a business and you were the CEO. And I keep coming back to what you were talking about when we were explaining the chief exports of the country. Could one answer be coming up with a real specialty, a new specialty inside the U.S. where we have a strength on the level that we might have had with steel back in the day or that Japan has now with cars and electronics?

Steve Ballmer: Well, I’m not going to go there with you. I think a lot of what happens in business happens in business. We are not all able to control it. That’s part of the brilliance of America’s entrepreneurial, capitalist society. I think that has served us very well. We do need to make sure that trade in the world is free and open. And if it’s not going to be free and open for others and for us, then it’s worth taking a look. But at the end of the day, I count on capitalism with a little bit of proper oversight from government to help these things work.

Todd Bishop: Steve Ballmer, thank you very much.

Steve Ballmer: Pleasure, Todd. Thanks for having me on Numbers Geek.

Todd Bishop V/O: Before we end the show, a quick fact-check. Remember the clip we played at the beginning, with President Trump describing the U.S. trade deficit?

President Trump: “Our country lost $800 billion last year with trade generally.”

Todd Bishop V/O: As you know now from this episode, that’s a lot higher than the numbers we’ve been discussing, in the range of $450 to $550 billion per year. Although he didn’t make this clear, President Trump was referencing the gap in the trade of goods alone, not including services, where the country runs a surplus that reduces the overall trade deficit. This number also doesn’t include the income from Americans abroad, as discussed earlier in the show.

So the next time you read or hear numbers on the trade gap, you can ask yourself, what exactly does that include? You’ll be able to put this into practice soon: New numbers showing the trade gap for 2018 are due out from the government in the coming weeks.

Todd Bishop: Numbers Geek is produced by GeekWire in partnership with Steve Ballmer and USAFacts. Numbers Geek graphic design by Killer Infographics. Theme music by Daniel L. K. Caldwell. Thanks to Clare McGrane and Frank Catalano for editing and production work on this episode. For more Numbers Geek episodes and videos, plus citations to the numbers we discuss, go to geekwire.com/numbersgeek. You can find interactive graphics, charts, and government data at usafacts.org, where you can also download the 2018 USAFacts annual report on the U.S. government and see page 46 for a deep dive on U.S. trade.

Thanks for listening to Numbers Geek. Don’t forget to rate and review and subscribe to the show in your favorite podcast app. I’m Todd Bishop, GeekWire editor. We’ll be back soon with another episode of Numbers Geek.

Conclusion: So above is the Numbers Geek: Steve Ballmer on the U.S. trade deficit, China’s role, and the impact on the economy article. Hopefully with this article you can help you in life, always follow and read our good articles on the website: Ngoinhanho101.com